Martin Luther’s 95 Theses: A Comprehensive Summary

On October 31, 1517, Martin Luther challenged church practices with his 95 Theses, initiating a religious revolution․ This document questioned indulgences and papal authority,

sparking the Protestant Reformation and profoundly impacting modern Christianity, even today․

Historical Context of the Theses

The early 16th century witnessed a Europe steeped in religious fervor, yet troubled by corruption within the Catholic Church․ The Renaissance had fostered a spirit of inquiry, and humanist scholars were re-examining classical texts, including the Bible, leading to questioning of established doctrines․ Germany, fragmented into numerous principalities, lacked a unified political structure, creating a climate where challenges to authority could take root․

The Church, facing financial pressures, increasingly relied on the sale of indulgences – certificates promising remission of temporal punishment for sins․ This practice, perceived by many as exploitative, fueled resentment․ Martin Luther, an Augustinian monk and professor at the University of Wittenberg, was deeply concerned with the theological implications of indulgences and the state of souls․ His personal struggles with faith and his meticulous study of scripture led him to believe that salvation was achieved through faith alone, not through works or monetary contributions․

The societal landscape of the time, coupled with the Church’s practices, created a fertile ground for dissent․ Luther’s 95 Theses weren’t born in a vacuum, but rather as a direct response to specific abuses and a growing theological conviction․

The Act of Posting: October 31, 1517

The traditional narrative depicts Martin Luther dramatically nailing his 95 Theses to the door of the All Saints’ Church in Wittenberg on October 31, 1517․ While this image is iconic, the historical reality is more nuanced․ Church doors served as public bulletin boards for announcements and scholarly disputations; posting theses was a common academic practice․

Luther’s intent wasn’t necessarily to initiate a public revolt, but rather to invite scholarly debate․ He enclosed a copy of the Theses with a letter to Archbishop Albrecht of Brandenburg, hoping to address his concerns about the sale of indulgences․ The act of posting, therefore, was a formal invitation to a theological discussion, a challenge to defend the Church’s practices․

However, the timing – coinciding with the eve of All Saints’ Day, a period of high church attendance – amplified the impact․ The Theses quickly spread beyond Wittenberg, initially through handwritten copies and, crucially, with the advent of the printing press, rapidly disseminated throughout Germany and beyond, igniting a firestorm of controversy․

The Church’s Practice of Indulgences

The practice of indulgences, prevalent in the late medieval Church, involved the remission of temporal punishment due to sin, granted through the Church’s authority․ Rooted in the belief in purgatory – a state of purification after death – indulgences offered a reduction of time spent there․ Initially, they were granted for acts of piety, like pilgrimages or charitable donations․

However, by Luther’s time, the system had become heavily commercialized․ Indulgences were increasingly sold for financial gain, often promoted by aggressive preachers who equated them with a guaranteed ticket to salvation․ Johann Tetzel, a prominent indulgence seller, famously proclaimed, “As soon as the coin in the coffer rings, a soul from purgatory springs!”

This monetization of grace deeply troubled many, including Luther, who viewed it as a corruption of true repentance and faith․ The Church argued indulgences merely shortened temporal punishment, not absolved guilt, but this nuance was often lost in the marketing․ Luther believed this practice misled the faithful and undermined the Gospel message․

What Were Indulgences?

Indulgences, within the Catholic Church’s framework, were essentially a way to reduce or eliminate the temporal punishment for sins whose guilt had already been forgiven․ This stemmed from the belief that sin had three consequences: eternal punishment (hell), forgiveness through confession, and temporal punishment (suffering in this life or purgatory)․ Indulgences addressed only the temporal aspect․

Originally, indulgences were granted for performing pious acts – going on pilgrimage, donating to charity, or participating in crusades․ Over time, they became increasingly associated with monetary contributions․ The Church maintained that indulgences didn’t forgive sins, but lessened the penalty due to sin, offering relief from purgatory’s duration․

However, the system became susceptible to abuse․ The sale of indulgences, particularly aggressive campaigns like those led by Johann Tetzel, raised concerns about their theological basis and ethical implications․ Luther’s critique wasn’t against the concept of remission of punishment itself, but against the commercialization and the false impression that indulgences could buy salvation․

The Spark of the Protestant Reformation

Martin Luther’s posting of the 95 Theses on October 31, 1517, is widely considered the catalyst for the Protestant Reformation, though it wasn’t immediately recognized as such․ Luther intended to initiate scholarly debate about the practice of indulgences, not to overthrow the Church․

The rapid dissemination of the Theses, facilitated by the newly invented printing press, quickly moved the debate beyond academic circles․ Copies spread throughout Germany and beyond, sparking widespread discussion and criticism of Church practices․ This accessibility was crucial; previously, dissenting views remained localized․

Luther’s challenge to papal authority, particularly regarding the sale of indulgences, resonated with many who felt alienated by the Church’s perceived corruption and worldliness․ His emphasis on individual faith and scripture as the ultimate authority laid the groundwork for a new theological perspective․ The initial reaction wasn’t outright condemnation, but a call for Luther to clarify his positions, setting the stage for further conflict and ultimately, a schism within Christendom․

The Core Arguments of the 95 Theses

Luther’s theses primarily critiqued indulgences, questioning papal power to remit penalties․ He stressed true repentance, faith, and God’s grace, challenging the church’s marketplace approach to salvation․

Thesis 1: Repentance and True Christian Life

Luther’s opening thesis fundamentally redefines the Christian life, centering it not on external rituals or indulgences, but on genuine inner repentance․ He argues that true Christian living isn’t about seeking release from penalties imposed by the Church, but about a continuous, heartfelt sorrow for sin and a commitment to following Christ․ This internal transformation, driven by faith, is the core of a meaningful spiritual existence․

He directly challenges the prevailing notion that salvation can be bought or earned through contributions or the purchase of indulgences․ Instead, Luther posits that repentance is a lifelong process, a daily dying to self and rebirth in Christ․ This emphasis on inward transformation directly opposes the external focus of the Church’s practices at the time, which prioritized outward observances and financial contributions․

Thesis 1 sets the stage for the entire document, establishing Luther’s core theological perspective․ It’s a call for a return to the authentic teachings of the Gospel, emphasizing the necessity of a personal relationship with God and a life lived in accordance with His will, rather than adherence to prescribed religious practices․ This foundational argument underpins all subsequent criticisms within the 95 Theses․

Thesis 21-40: Criticisms of Papal Authority Regarding Indulgences

These theses represent a direct assault on the Pope’s authority to grant indulgences, arguing that such power isn’t found in Scripture or early Church tradition․ Luther contends the Pope can only remit penalties he himself imposed, not those decreed by divine law․ He challenges the very foundation upon which the sale of indulgences rested, questioning the Pope’s ability to release souls from purgatory․

Luther meticulously dismantles the theological justifications for indulgences, asserting that true repentance, not financial payment, is the path to forgiveness․ He criticizes the misleading promises made to those purchasing indulgences, suggesting they create a false sense of security and discourage genuine contrition․ He points out the disparity between the wealth accumulated by the Church through indulgences and the spiritual poverty of its flock․

These theses aren’t merely theological objections; they’re a challenge to the Church’s economic practices and its abuse of power․ Luther’s arguments highlight a fundamental disconnect between the Church’s claims and the realities experienced by ordinary Christians, fueling the growing discontent that would ultimately ignite the Reformation․

Thesis 41-60: The Nature of True Treasure and Christian Charity

Within these theses, Luther shifts focus from directly attacking indulgences to redefining what constitutes genuine spiritual wealth․ He argues that true treasure isn’t found in the Church’s coffers, amassed through the sale of indulgences, but resides in the grace of God and the inner transformation of the believer․ He champions the virtues of Christian charity, emphasizing that giving to the poor and needy is far more valuable than purchasing forgiveness․

Luther contrasts the superficial piety fostered by indulgences with the authentic faith expressed through acts of love and compassion․ He criticizes the Church’s prioritization of financial gain over genuine spiritual concern for its followers․ He suggests that the Church should be focused on alleviating suffering and promoting social justice, rather than exploiting people’s fears of purgatory․

These theses present a compelling alternative to the Church’s materialistic worldview, advocating for a faith rooted in humility, generosity, and a sincere commitment to serving others․ Luther’s emphasis on Christian charity foreshadows the social reforms that would become central to the Protestant movement․

Thesis 61-85: Challenging the Effectiveness of Indulgences

These theses directly dismantle the purported efficacy of indulgences, questioning their ability to genuinely remit punishment for sins․ Luther argues that indulgences offer a false sense of security, leading people to believe they can buy their way into heaven without true repentance or faith․ He insists that God’s forgiveness is not contingent upon monetary payment, but is freely offered through grace alone․

He challenges the Pope’s authority to grant indulgences, asserting that the power to forgive sins rests solely with God․ Luther contends that indulgences cannot bind or loose anyone in heaven, as this power belongs exclusively to divine judgment․ He further criticizes the misleading claims made by indulgence preachers, who often exaggerate their benefits and exploit the ignorance of the faithful․

Luther’s arguments in these theses expose the theological flaws and practical abuses inherent in the practice of selling indulgences, laying the groundwork for his broader critique of the Church’s authority and doctrines․

Thesis 86-95: Concerns about the Impact on the Faithful

These final theses express Luther’s deep pastoral concern for the spiritual well-being of the common people․ He fears that the widespread sale of indulgences is misleading the faithful, fostering a dangerous reliance on external rituals rather than genuine faith and repentance․ Luther worries that Christians are being robbed of their hard-earned money under false pretenses, believing they are securing salvation when, in reality, they are being deceived․

He laments the potential for spiritual harm caused by the abuse of indulgences, arguing that they distract from the true treasures of the Christian life: faith, hope, and love․ Luther expresses his desire for open debate on these issues, inviting scholars and theologians to examine his arguments and challenge his conclusions․ He concludes with a plea for humility and a recognition of the limitations of human authority in matters of faith․

Ultimately, these theses reveal Luther’s commitment to the spiritual welfare of his flock and his desire to restore the purity of the Gospel message․

Key Theological Concepts in the Theses

Luther’s theses implicitly champion Sola Scriptura, Sola Fide, and Sola Gratia․ Repentance is central, rejecting reliance on indulgences for forgiveness, emphasizing faith and God’s grace alone․

Sola Scriptura (Scripture Alone)

The principle of Sola Scriptura, meaning “Scripture alone,” stands as a cornerstone of Luther’s theological challenge and is deeply embedded within the spirit of the 95 Theses․ Luther argued that the Bible is the ultimate and sole authority for Christian belief and practice, rejecting the equal authority claimed by the Pope, Church tradition, or ecumenical councils․

This wasn’t a rejection of all tradition, but a firm assertion that tradition must be judged and corrected by Scripture, not the other way around․ Luther believed that the Church had, over time, added layers of human interpretation and practice that obscured the pure Gospel message found in the Bible․ He meticulously returned to the original biblical texts, particularly the Psalms which he read frequently, to formulate his arguments․

By prioritizing Scripture, Luther aimed to restore a direct relationship between the believer and God, unmediated by the institutional Church․ He challenged the notion that the Church possessed the exclusive right to interpret God’s word, empowering individuals to engage with the Bible directly․ This emphasis on individual interpretation, guided by the Holy Spirit, became a defining characteristic of the Protestant Reformation and continues to shape Protestant theology today․

Sola Fide (Faith Alone)

Central to Luther’s critique, and interwoven with Sola Scriptura, is the doctrine of Sola Fide – “faith alone․” This principle asserts that salvation is received through faith in Jesus Christ alone, and not through good works or the purchase of indulgences․ Luther vehemently opposed the Church’s practice of selling indulgences, believing they fostered a false sense of security and undermined the true meaning of repentance and grace․

He argued that human efforts to earn salvation are futile; salvation is a free gift from God, offered through Christ’s sacrifice․ This wasn’t to diminish the importance of good works, but to clarify their result of genuine faith, not their cause․ True faith, Luther maintained, naturally produces good works as evidence of a transformed heart․

The 95 Theses directly challenged the idea that indulgences could remit God’s punishment for sin, emphasizing that only God’s grace, received through faith, could offer true forgiveness․ This concept liberated believers from the burden of legalistic requirements and focused their attention on a personal relationship with God, based on trust and reliance on His mercy․

Sola Gratia (Grace Alone)

Closely linked to Sola Fide, the principle of Sola Gratia – “grace alone” – forms a cornerstone of Luther’s theological challenge․ This doctrine proclaims that salvation is entirely a gift from God’s unearned favor, bestowed upon humanity solely out of His love and mercy․ It rejects any notion that humans can contribute to their own salvation through merit, works, or inherent righteousness․

Luther argued that humanity is inherently sinful and incapable of achieving salvation through its own efforts․ God’s grace, therefore, is not a response to human goodness, but a proactive and undeserved gift offered to all․ This grace is freely given through faith in Jesus Christ, who bore the penalty for human sin․

The 95 Theses implicitly challenged the Church’s system of indulgences, which suggested that salvation could be purchased or earned․ Luther believed this undermined the concept of grace, portraying God as a transactional figure rather than a loving Father․ True repentance, he insisted, stems from recognizing one’s utter dependence on God’s grace, not from attempting to appease Him through monetary offerings․

The Importance of Repentance

Central to Luther’s arguments within the 95 Theses is a redefinition of true repentance․ He vehemently opposed the superficial and externally-focused penances commonly practiced by the Church, viewing them as inadequate substitutes for genuine inner transformation․ Luther insisted that true repentance isn’t merely about confessing sins and performing prescribed acts of atonement, but a profound, ongoing process of turning away from sin and towards God․

This internal shift, he argued, necessitates a heartfelt sorrow for sin, coupled with a firm resolve to live a life pleasing to God․ It’s a continuous struggle, fueled by faith and guided by Scripture․ Luther believed the Church’s emphasis on indulgences actually hindered genuine repentance, offering a false sense of security and discouraging individuals from confronting their own sinfulness․

He posited that the focus should be on cultivating a contrite heart, acknowledging one’s complete dependence on God’s grace for forgiveness, and striving to live a life reflecting that renewed faith․ This internal work, not external rituals, is the essence of true repentance․

The Immediate Aftermath and Spread of the Theses

Luther’s 95 Theses rapidly disseminated thanks to the printing press, sparking immediate debate․ Initial Church reactions ranged from dismissal to outrage, prompting Luther into further theological discussions and writings․

Dissemination and Printing

The rapid spread of Martin Luther’s 95 Theses beyond Wittenberg was largely due to the relatively new technology of the printing press․ Before 1517, disseminating ideas relied heavily on laborious hand-copying, limiting reach and speed․ However, Johannes Gutenberg’s invention allowed for the quick and inexpensive production of pamphlets and broadsides․

Luther’s theses were initially intended for academic debate, but copies were quickly printed in both Latin and German, making them accessible to a wider audience․ These printed versions circulated throughout Germany and beyond, reaching scholars, clergy, and even laypeople․ The printing press acted as a powerful catalyst, transforming a local dispute into a widespread public discussion․

Early printed editions weren’t always accurate, with variations appearing as printers made corrections or alterations․ Despite these inconsistencies, the core message of Luther’s critique of indulgences and papal authority resonated with many, fueling growing discontent with the Church․ The ability to mass-produce and distribute the 95 Theses was crucial in igniting the Protestant Reformation, demonstrating the power of information dissemination in challenging established institutions․

Initial Reactions from the Church

The Church’s initial response to Luther’s 95 Theses was, surprisingly, not immediate outrage, but rather a degree of dismissal․ Many within the Church hierarchy initially viewed the theses as the concerns of a relatively unknown Augustinian monk, and a localized academic dispute․ They underestimated the potential for widespread impact․

However, as printed copies of the theses circulated and sparked debate, concerns began to grow․ Johann Tetzel, the Dominican friar whose indulgence sales Luther specifically criticized, responded with counter-arguments, defending the practice and attacking Luther’s character․ This marked the beginning of a public exchange of views․

Higher-ranking officials, including Luther’s own Augustinian superiors, urged him to retract his statements․ The Vatican initially sought a diplomatic solution, requesting Luther to explain his views․ This period was characterized by attempts to contain the controversy, but the momentum was building, and the debate quickly escalated beyond the Church’s initial control, setting the stage for further conflict and eventual condemnation․

Luther’s Subsequent Debates and Writings

Following the dissemination of the 95 Theses, Luther engaged in a series of increasingly public debates and prolific writing․ He defended his positions against papal legates like Cardinal Cajetan, refusing to recant unless proven wrong by Scripture – a bold stance challenging papal authority․

These debates, particularly the Leipzig Disputation in 1519, were pivotal․ Luther argued directly against scholastic theologians, further solidifying his theological positions and gaining wider support․ Simultaneously, he began publishing a series of treatises, including “On Christian Liberty” and “The Babylonian Captivity of the Church,” outlining his core beliefs․

These writings systematically attacked perceived abuses within the Church, advocating for Sola Scriptura, Sola Fide, and Sola Gratia․ Luther’s vernacular writings, particularly his German translation of the New Testament, made his ideas accessible to a broader audience, fueling the Reformation’s momentum and solidifying his role as its central figure․

Long-Term Impact and Legacy

Luther’s actions ignited the Protestant Reformation, reshaping Christianity and European politics․ His legacy continues to influence modern religious thought, sparking ongoing discussions about faith and authority today․

The Protestant Reformation’s Expansion

Following the initial dissemination of Luther’s 95 Theses, the ideas rapidly spread beyond Wittenberg, fueled by the newly invented printing press․ This allowed for quick and widespread distribution of his writings, reaching a broad audience eager for religious reform․ Initially, support coalesced within German states, with princes seeing an opportunity to assert independence from both the Holy Roman Emperor and the Catholic Church․

The Reformation wasn’t monolithic; different interpretations of Luther’s teachings emerged, leading to the development of various Protestant denominations, including Calvinism and Anabaptism․ These movements further fragmented the religious landscape of Europe․ Switzerland became a key center for Reformation thought, particularly with the work of Huldrych Zwingli and John Calvin․

Conflicts inevitably arose, manifesting in religious wars across Europe, such as the Schmalkaldic War in the Holy Roman Empire and the French Wars of Religion․ These conflicts weren’t solely theological; political and economic factors played significant roles․ The Reformation’s expansion fundamentally altered the power dynamics of Europe, contributing to the rise of nation-states and challenging the centuries-old authority of the Papacy․

Influence on Modern Christianity

Martin Luther’s challenge to the Catholic Church profoundly reshaped Christianity, giving rise to Protestantism and irrevocably altering the religious landscape․ The emphasis on Sola Scriptura – Scripture alone – became a cornerstone of Protestant theology, empowering individuals to interpret the Bible directly, diminishing the Church’s exclusive authority․ This fostered a spirit of independent thought and biblical literacy․

The concept of Sola Fide – faith alone – revolutionized understandings of salvation, shifting focus from good works and sacraments to a personal relationship with God through faith․ This impacted ethical frameworks and individual spirituality․ Furthermore, Luther’s advocacy for vernacular translations of the Bible made scripture accessible to common people, breaking down linguistic barriers to religious understanding․

Modern Christianity continues to grapple with the legacy of the Reformation․ Denominations tracing their roots to Luther’s movement – Lutheranism, Presbyterianism, and others – represent significant branches of the Christian faith․ Even within Catholicism, the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965) incorporated some reforms echoing Reformation concerns, demonstrating the enduring influence of Luther’s initial challenge․

The 95 Theses in Popular Culture

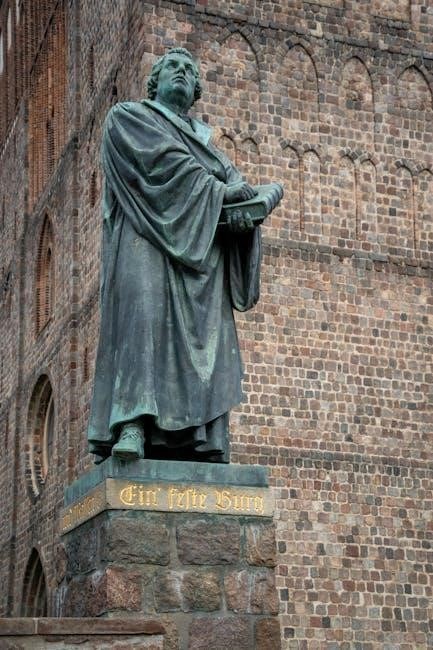

Martin Luther’s 95 Theses, though a theological document, have transcended religious circles to become a potent symbol of dissent and challenging established authority․ The image of Luther nailing the theses to the church door in Wittenberg is a frequently referenced historical moment, often used metaphorically to represent acts of defiance and initiating significant change․

Numerous artistic representations depict this pivotal event, solidifying its place in collective memory․ The story has been dramatized in films, novels, and plays, often portraying Luther as a courageous individual standing up against a corrupt system․ These portrayals, while sometimes romanticized, contribute to the ongoing fascination with his story․

The “95 Theses” format itself has been adopted in various contexts as a means of presenting a list of grievances or proposals for change․ From academic critiques to political manifestos, the structure lends itself to concise and impactful argumentation․ The anniversary of the posting – October 31st – is often marked by commemorative events and discussions, keeping Luther’s legacy alive in contemporary discourse․

The Continuing Relevance of Luther’s Concerns

Though penned over five centuries ago, Martin Luther’s concerns articulated in the 95 Theses retain surprising relevance in the 21st century․ His core challenge to unchecked authority, particularly regarding spiritual matters, resonates in an age grappling with issues of institutional accountability and transparency․

Luther’s emphasis on individual conscience and direct access to scripture – Sola Scriptura – continues to fuel debates about religious interpretation and the role of intermediaries․ The questioning of financial exploitation within religious institutions, central to his critique of indulgences, echoes in contemporary scrutiny of wealth accumulation and ethical practices within various organizations․

Furthermore, Luther’s insistence on genuine repentance and faith, rather than ritualistic adherence, speaks to a broader human desire for authentic spirituality․ His legacy prompts ongoing reflection on the balance between tradition and individual belief, and the importance of critically examining power structures that claim absolute authority․ The core themes of his protest remain powerfully pertinent․